Posted: 01/24/2019

Alabama Deer:

How Can We Keep Them Free from Chronic Wasting Disease?

By Ray Metzler

Certified Wildlife Biologist, Alabama Forestry Commission

Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) has now been confirmed in three deer on two sites in Mississippi. The first confirmation in February 2018 was just east of the Mississippi River – as far from Alabama as it could be and still be in Mississippi. A second incidence was announced on October 19, 2018, of a deer in Pontotoc County in northeast Mississippi, approximately 47 miles from the Alabama state line in Marion County. A third deer recently tested positive within the CWD management zone in western Mississippi.

More recently, the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency detected CWD in the Tennessee counties of Fayette and Hardeman. As of January 23, 2019, a total of 91 deer had tested positive for CWD in those two counties. Franklin, Colbert, and Lauderdale counties in Alabama are all within 50 miles of these Tennessee CWD occurrences.

The discovery of CWD in Mississippi and Tennessee has increased the level of concern among southeastern state fish and wildlife agencies, land managers, hunting clubs, and hunters. Before these determinations in our neighbor state to the west, CWD had not been detected in the deep south – northern Arkansas was as far south as the disease had been discovered east of the Mississippi River. Although over 6,600 deer have been tested for CWD in Alabama since 2002, to date, none have tested positive.

CWD is an infectious, communicable, and always fatal neurological disease of members of the family Cervidae (which includes deer, elk, and moose). This fact is the primary reason why Alabama hunters should be very concerned about this issue and be proactive to ensure CWD does not make its way to our state. Disease experts classify CWD as a transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE) along with other related diseases such as scrapie in sheep, bovine spongiform encephalopathy in cattle, and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in humans. TSEs are believed to be caused by misfolded ‘prion’ proteins. Research has shown these prions to be ‘long lived’ and very difficult to destroy. Procedures such as heating the prions to temperatures exceeding 1,100° F or disinfecting with bleach haven’t proven to be completely effective. A recent study reported that exposing the prions to temperatures greater than 900° F for at least four hours would destroy them. A great deal of research has taken place since being first recognized in 1967 at a wildlife research facility in Fort Collins, Colorado, but there is still a lot to be learned.

Research indicates the incubation period for CWD is typically 17-18 months or longer. These mis-formed prions can apparently be shed from infected animals in saliva, urine, blood, soft-antler material, and feces. Animals can become infected through direct contact with another animal or indirectly from contaminated material in the environment.

Testing for CWD requires post-mortem examination of the brain or lymph nodes from the throat. There are no reliable live-animal testing procedures, and no known vaccine or treatment exists. Alabama began testing hunter-harvested, road-killed, and those deer showing signs of emaciation and/or neurological abnormalities in 2002. These collections have taken place each year, with the exception of two years when federal funding for this activity was lost. No deer from Alabama have tested CWD positive since testing began.

A white-tail deer and an elk in north Arkansas both tested CWD-positive in February 2016. The Arkansas Game and Fish Commission quickly implemented their CWD response plan which included outlining a CWD Management Zone. They began collecting additional specimens for testing to determine how prevalent the disease was within the management zone. Surprisingly, they determined that approximately 23 percent of the samples tested were CWD-positive. Because of the extended incubation period of CWD, it has long been recognized that deer less than a year of age could not test positive for the disease. However, even deer between seven and ten months old included in the Arkansas samples resulted in positive detection for CWD at the same 23 percent infection rate. This fact indicates that CWD may have been present and gone undetected for as long as 10 years. Ten counties in Arkansas have now been confirmed as CWD-positive since 2016.

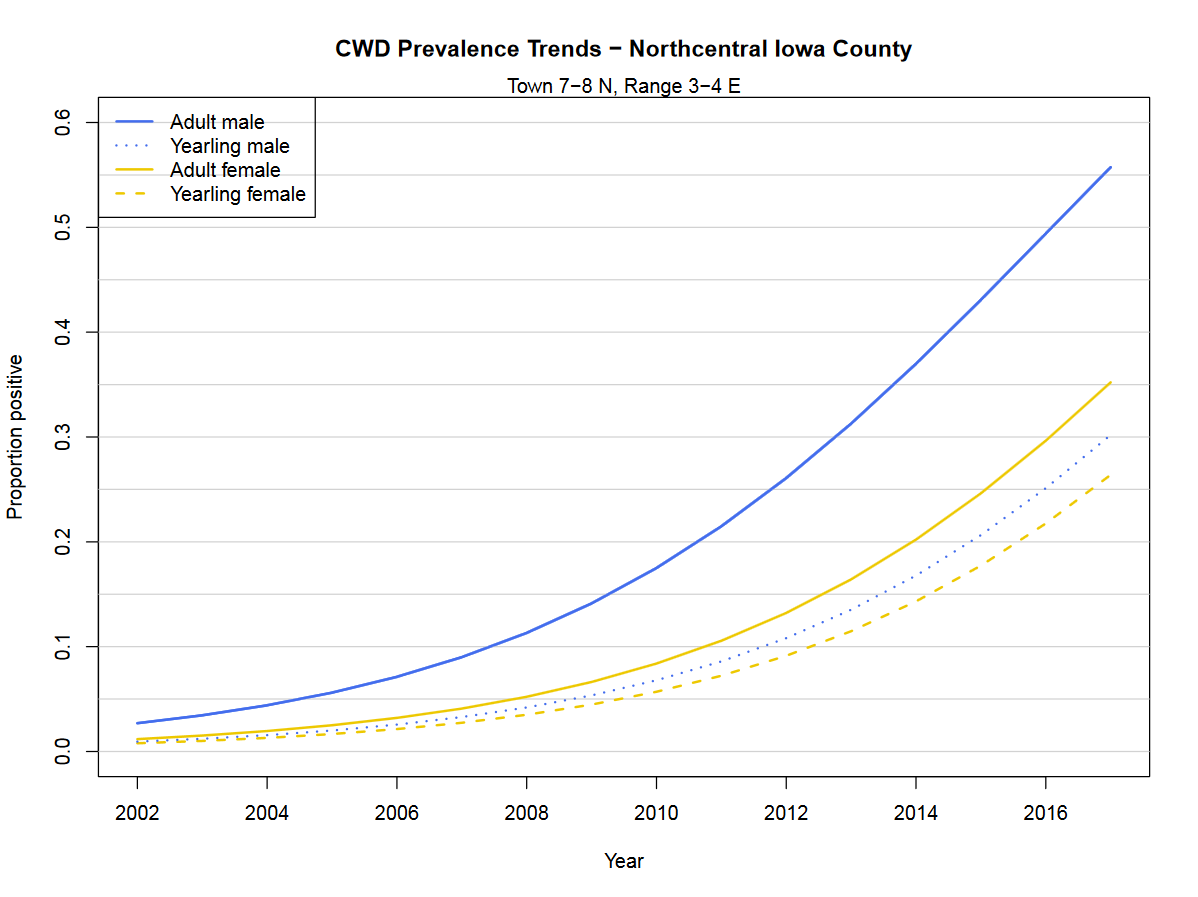

The longer the disease has been present in an area, prevalence of CWD increases. The endemic areas in Colorado and Wyoming have prevalence rates ranging from 20-40 percent. Figure 1 demonstrates the significant increase in prevalence in northcentral Iowa County, Wisconsin, since the initial detection of CWD in 2002. Greater than 50 percent of adult bucks in this local area were found to have this always fatal neurological disease. This data from Wisconsin is alarming to me as a biologist and suggests the prevalence rate will continue to increase. Only time will tell if there is some maximum rate at which the disease will be found in a given population.

Prevalence rates greater than 50 percent for a disease that is always fatal would certainly have negative impacts to population density, hunter satisfaction, and economics – all of which are important factors in modern wildlife management. Many experts say that the best defense against CWD is to employ an offense that keeps it from arriving in our state.

Figure 1. White-tailed deer CWD prevalence rates in northcentral Iowa County, Wisconsin. Graph taken from dnr.wi.gov on June 25, 2018.

Figure 1. White-tailed deer CWD prevalence rates in northcentral Iowa County, Wisconsin. Graph taken from dnr.wi.gov on June 25, 2018.

One might ask, how would CWD arrive in Alabama if we don’t have it already? Research indicates two potential vectors as causal agents for CWD infection in Alabama. Importation of CWD-infected live deer, or certain body parts of infected deer are the primary concerns.

The need for the live animal importation ban is obvious to most hunters and conservationists. In the early 1970s, the Alabama Division of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries was proactive with the implementation of a state law prohibiting the importation of any live deer into the state. While this law has not completely stopped the importation of live animals, it has certainly caused some folks to think twice before attempting to import a live deer into Alabama. A recent federal court case involving a violation of the importation ban by a licensed game breeder resulted in a conviction and fine of $750,000.

Importation of body parts of harvested deer from all states, Canadian provinces, and foreign countries was recently banned. This ban on body parts is sometimes questioned by individuals outside of the wildlife management arena. Remember, the infected prions are very difficult to destroy and can be distributed into the environment from infected body parts such as brain and spinal cord tissue, large bones, and lymph nodes that have been discarded. For this reason, it is important to bring only deboned meat, antlers (without velvet), clean skull plates, and hides into Alabama from any deer killed within a CWD-positive area in other states. Recent research indicates healthy animals may be able to pick up the prions from soils and even plant materials that have been infected from urine, saliva, blood, soft-antler material, and feces.

Although a direct link between CWD in deer and illness in humans has not been documented, both the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) urge caution and recommend testing of deer harvested in CWD positive areas. Mad cow, a similar disease as CWD has been able to move from cattle to humans, resulting in at least 30 deaths worldwide. In 2017, Canadian researchers claimed to have observed CWD in macaque monkeys who had eaten infected deer meat, but in 2018 the National Institute of Health reported that there was no transmissibility in macaques.

A recent review of many studies could not rule out the possibility of CWD transmission to humans in the future. More information is needed about incubation periods of CWD prions and possible human illness. This is one of the reasons that caution must be used when hunting in and consuming venison from CWD-positive areas. Information from CWD-positive areas in Wisconsin indicate many deer go untested and one must assume that hunters and their families are ingesting venison that could harbor the mis-formed prions. As a hunter and biologist, following the WHO and CDC guidelines makes sense to me.

Deer hunting in Alabama will be forever changed if CWD finds its way to our state. The Alabama Division of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries recently unveiled an updated CWD Strategic Surveillance and Response Plan. Available at www.outdooralabama.com, this plan is something that each hunter should read and understand. Some of the highlights of the plan include establishing a five-mile radius core-zone around a confirmed CWD-positive cervid location, and implementing, but not limited to, the following regulations:

- Mandatory check stations to sample hunter-harvested deer.

- Ban the movement of whole deer carcasses harvested inside the core-zone, to areas outside of the core-zone.

- Permitting of meat processors and taxidermists to minimize the risk of CWD prions leaving the core-zone.

- Prohibit all supplemental feeding within all counties located within or contacting the core-zone.

- Finalize deer carcass disposal regulations to require discarded parts to be bagged and deposited into a lined landfill or buried on-site at least 8 feet deep.

Banning of supplemental feeding within a core-zone is one of the first steps generally taken by a state game and fish agency when CWD is discovered. Baiting and supplemental feeding have been discussed and debated in Alabama for many years by professional biologists, hunters, and our legislative representatives in Montgomery. In fact, legalized baiting came within one vote of passing during the 2018 legislative session. The ban of supplemental feeding in the response plan is a reaction to a stimulus (CWD) that should generate some questions. First and foremost, should we as hunters, hunting clubs, landowners, and managers be proactive by eliminating supplemental feeding while Alabama is still CWD free? This is a question that every hunter, hunting club, and landowner should ask themselves. The Alabama Chapter of the Wildlife Society, a group comprised of professional wildlife biologists from state and federal agencies, academia, conservation groups, and private corporations approved a position statement in 2012 that opposes baiting and feeding of game species by the general public. This debate will probably continue in the future, but the consequences of supplemental feeding and baiting could exponentially increase if CWD is discovered in Alabama.

CWD detection has proven to have negative impacts on local economies, especially in sparsely populated counties that rely heavily on visiting hunters. Will hunters continue to lease property if CWD is detected in an area? If not, the landowner will be negatively impacted and local businesses will suffer financially due to fewer hunters being present during deer season. The cumulative effects of CWD could be devastating to a local economy and the economic impact that whitetail deer hunting generates in Alabama.

Biosecurity issues resulting from the detection of CWD should be a concern for all hunters in Alabama, not just those in a CWD-positive area. Many hunters harvest deer in areas away from their residence, either taking the carcass home to process or to a meat processor near home. The detection of CWD would require all deer killed in the core zone to be deboned within the core zone, and then disposal of the carcass by placing it in a plastic bag in a lined landfill or buried on site at least 8 feet deep. These biosecurity challenges would be daunting, requiring hunters and the Division of Wildlife & Freshwater Fisheries to be completely engaged in a process to ensure this fatal disease does not expand out of the core zone.

As a hunter, I would much rather be proactive and do everything possible to ensure CWD does not make its way to Alabama instead of having to endure the biosecurity and testing challenges. I am one of those guys that just wants to kill a deer and eat it, without having to worry about it causing illness to me or my family.

Alabama hunters should be thankful that CWD has not yet been detected and be supportive of all efforts to ensure it is not brought to the state in the future. Report any known violations of Alabama’s ban on importation of live cervids or illegal body parts to the Division of Wildlife & Freshwater Fisheries by calling the Gamewatch number or your local district office. Each and every hunter in the state should have a vested interest in protecting the future of hunting as we know it today by minimizing the risk of CWD becoming a part of the Alabama landscape.

To find out more about CWD, visit the following websites:

Chronic Wasting Disease Alliance at http://cwd-info.org/

Wildlife & Freshwater Fisheries Division of the Alabama Department of Conservation & Natural Resources at https://www.outdooralabama.com/node/2517

Alabama Cooperative Extension System at https://store.aces.edu/ItemDetail.aspx?ProductID=19675